Catholics talk a lot about sacraments. But those unfamiliar with Catholic teaching may not know what a sacrament is, and even lifelong Catholics may not be able to clearly define this term when asked. So, what exactly is a sacrament, and what are the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church?

It is an outer sign of an inner grace. It is the visible, physical, and even material form of an invisible reality. For example, in Baptism, the form is water, but the inner reality is cleansing from the stain of original sin. In the Eucharist, the form is bread and wine, but the invisible reality is Christ’s Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity entering into us.

Sacraments aren’t magic formulas or good luck charms; their physical form affirms the incarnational nature of our faith. After all, God himself became incarnate in the person of Jesus Christ. Therefore, it is fitting that he continues to extend his grace to us through both spiritual and material means.

The Catholic Church officially recognizes seven sacraments; most practicing Catholics will receive most of these sacraments throughout their lives. The sacraments fall into three basic groupings:

Read on to discover what these seven sacraments are and to learn more about each one.

This first grouping of sacraments are just what they sound like: those that initiate Christians into the life of the Church.

Baptism is the sacrament by which a person is cleansed of original sin and made a member of God’s family, the Church. This is done with holy water and in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The Rite of Baptism also includes anointing with the oil of the catechumens as well as chrism oil. Most often, a priest or deacon will perform the baptism, but in extreme or urgent circumstances, other members of the Church can be permitted to administer the sacrament.

In Catholic families (as well as in some Protestant denominations), baptism is most commonly administered at infancy, so that the child can receive the graces of this sacrament as early as possible (why delay being cleansed of original sin and initiated into the family of God?). But if someone didn’t grow up in a religious family and wishes to become a member of the Catholic Church, they can receive Baptism as an adult after a period of formation known as RCIA or OCIA (the Rite or Order of Christian Initiation for Adults).

To recap, the Sacrament of Baptism:

Confirmation comes from the Latin word confirmare, which means “to strengthen.” Christians who have been baptized and instructed, or catechized, in the faith now receive this sacrament to strengthen that faith and equip them for service in the Church and the world.

Children who grow up in the Church typically receive the Sacrament of Confirmation as an early teen after years of religious education, or catechesis, which instructs them in the doctrines and practices of the faith. For those who convert to Catholicism as adults, they are usually confirmed at the same time they are baptized. For baptized Christians who convert to Catholicism, they will receive confirmation when they are formally received into the Church.

During the sacramental rite, the bishop or priest will address each of the confirmandi—candidates eligible for confirmation—by their chosen saint’s name and anoint them with chrism oil. While the confirmandi would have originally received the Holy Spirit at Baptism, Confirmation is a new impartation of the Spirit that strengthens those baptismal gifts.

In summary, confirmation:

The Eucharist is the Source and Summit of the Christian life; for Catholics, it’s our daily bread, the supernatural “manna” that sustains us on our spiritual journey toward heaven. St. Thomas Aquinas appropriately described the Eucharist as the “Sacrament of Sacraments,” because in it we receive the Person of Jesus Christ—His Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity.

Catholics receive the Eucharist for the first time at their First Holy Communion, which for Catholics raised in the Church usually happens at around age seven or eight. This is after First Communicants receive their first Sacrament of Reconciliation (also known as Confession—more on that below!). Adult converts to the faith will receive their First Communion when they are formally received into the Church, which is usually when they are also confirmed.

Catholics can receive the Eucharist during Holy Communion at Mass as often as every day. The only conditions are that they observe a one-hour Eucharistic fast (except for water and medicine) before receiving Communion and that they are not aware of any mortal sin on their conscience. If they are aware of serious sin, they just need to go to confession before receiving Communion again.

To summarize, the Eucharist:

The Sacraments of healing are those through which we are spiritually healed from sin and restored to grace (Confession) and given strength to endure (or sometimes be healed from) our physical suffering.

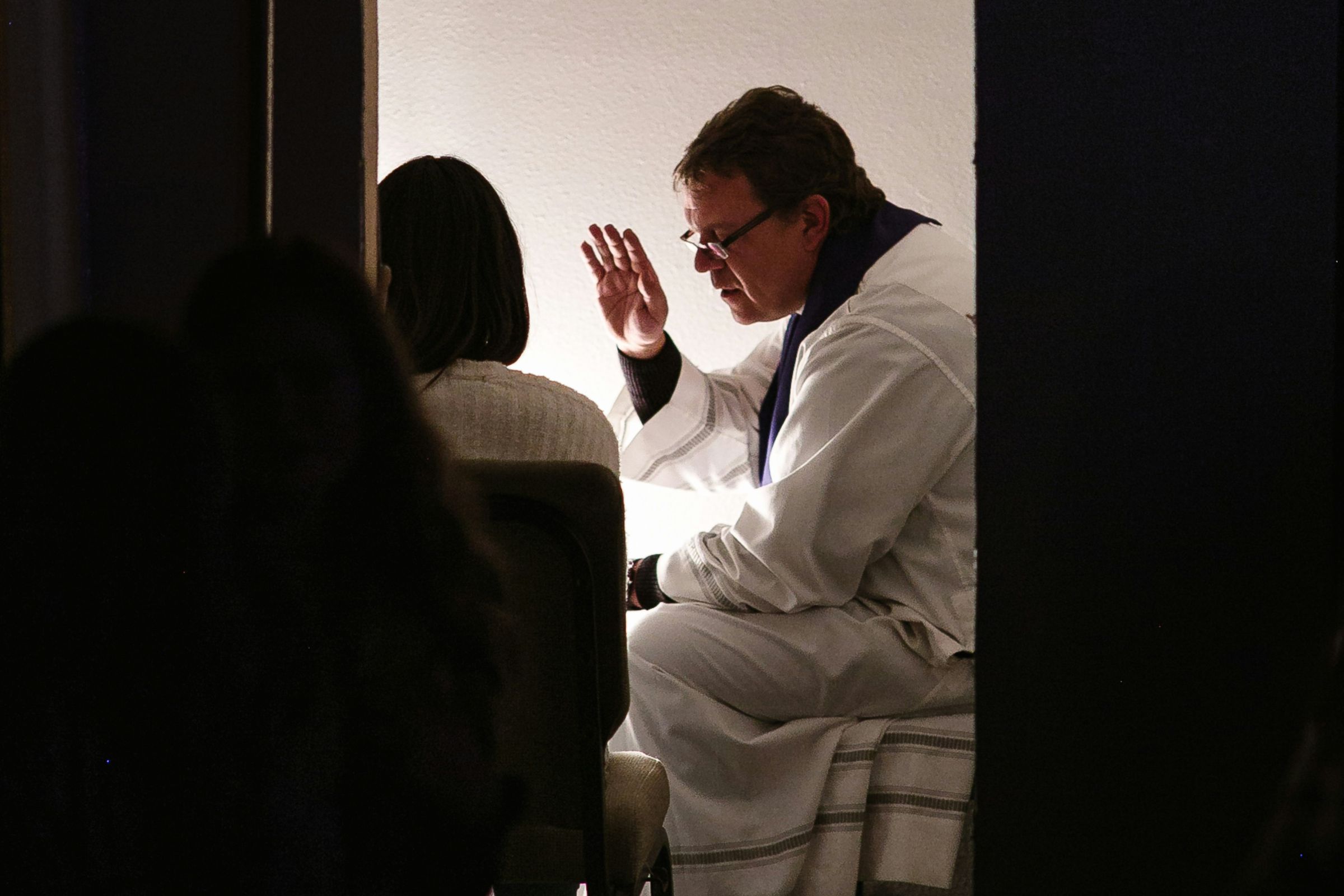

The Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation, more commonly known as Confession, is the sacrament by which Catholics confess their sins and receive absolution from a priest. It’s not the priest himself who forgives sins, but God administering his grace sacramentally through the priest. And it’s this grace that strengthens penitent Catholics to remain in a state of grace—free from mortal sin and in friendship with God.

If a Catholic commits a mortal sin—a sin that is serious, that they were fully aware of, and that they freely chose—they need to go to confession and repent of that sin to be restored to a state of grace (which includes being able to receive Holy Communion). While not required, it’s also strongly recommended that Catholics confess venial sins (non-mortal sins), because making use of the grace of the sacrament strengthens Catholics to resist temptation to sin, whether venial or mortal.

Before going to the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation, Catholics will often conduct an examination of conscience to help them remember the sins they want to confess. After confessing them to a priest, they will receive a penance from him, which is a way to help correct the wrong they’ve done and grow in their relationship with God. An example of this is apologizing to someone they’ve hurt or praying specific prayers. Finally, they will make an act of contrition, and the priest will grant them absolution, which absolves them from their sins by the authority Christ gave to His Church.

To recap, the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation:

The Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick is commonly associated with the Last Rites, but this sacrament is not limited to the end of one’s life. Anyone who is seriously ill can receive the Anointing of the Sick as a way of receiving strength to face their suffering with courage and hope, even if God doesn’t heal them physically.

The Anointing of the Sick is also a way to unite the sick person’s sufferings with Christ’s, giving them the grace to use their suffering as a means of serving the Church both with their prayers and by their witness to resurrection hope. This affirms their dignity as human beings created in God’s image, regardless of infirmity or physical limitation.

When administering this sacrament, a priest anoints the sick person’s forehead and hands with the Oil of the Sick and blesses them. If this sacrament is part of the Last Rites, Confession and Holy Communion will also be offered (if the dying person is able).

In summary, the Anointing of the Sick:

The Sacraments of Service are those through which we serve the Church and help build up the Kingdom of God:

These sacraments are directly related to one’s vocation, or their life’s calling from God. This is not to exclude single people; those who have not yet married nor discerned a vocation to the priesthood or religious life are still fully members of the Church. They can serve the Kingdom of God in a unique way through the freedom their singleness provides. This freedom includes the option to discern and enter into either of the two main vocations at any point in their lives.

In the Sacrament of Holy Matrimony, a man and a woman witness to Christ’s love for his Bride, the Church, through the covenant they make to each other. Their marriage commitment is also a reflection of the Holy Trinity, who is a community of persons bound in love.

Because marriage is a sacrament, it becomes a tangible means of grace for husbands and wives that strengthens them to love, serve, and support one another throughout their lives in their vocations as lay people. It also gives them grace to extend that love to any children that God gives them as well as their broader community and society as a whole. After all, the family is the basic building block of society!

While a priest officiates the wedding Mass or ceremony, in which the bride and groom exchange vows, the actual sacrament of marriage is one which the husband and wife confer on each other in the martial embrace. (If this is a new concept for you, then you should check out Pope St. John Paul II’s teaching on Theology of the Body.)

To summarize, the Sacrament of Holy Matrimony:

The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines Holy Orders this way:

Holy Orders is the sacrament through which the mission entrusted by Christ to his apostles continues to be exercised in the Church until the end of time: thus it is the sacrament of apostolic ministry.

Holy Orders are the sacrament by which a man is ordained as a deacon, priest, or bishop, commissioned to serve God and the Church in this specific office. Because these offices are directly related to one’s vocation, becoming a priest or deacon is not merely a matter of choice, like how one would choose a career. Instead, it is a generous and self-sacrificial response to God’s calling (similar to the call of matrimony), in response to His total and self-giving love.

This sacrament is celebrated during the Rites of Ordination, which takes place during a Mass. The rite includes the “laying on of hands” on the candidate by the bishop— “an ancient Biblical gesture beseeching God to empower the candidate by the Holy Spirit”—followed by a prayer of consecration, investing the new priest with his garments (the stole and chasuble), and anointing his palms with the Oil of Chrism.

If you’re wondering, What about those who are not called to neither marriage nor the priesthood (like nuns), rest assured that religious life and consecrated virginity are equally valid vocations, by which Catholics discern God’s call on their lives and profess vows in accord with that vocation to serve the Church. However, these do not involve the Sacrament of Holy Orders, which specifically ordains a man to the office of the diaconate or the priesthood.

To recap, the Sacrament of Holy Orders:

You now have a basic understanding of the seven sacraments, but there is so much more to sacramental theology! For further reading, see the Catechism of the Catholic Church.